Python priestess

of Malawi in

the sacred pool.

By an unknown

Chewa artist.

Python women and rain shrine priestesses were the primary spiritual leaders in old Malawi.

In Zimbabwe, too, priestesses were major figures. Kasamba founded a hilltop sanctuary of the Goba people in the distant past.

The Nehandas (lion oracles) were named after an originating princess who fled to a rocky shrine in the Mazoe valley in the 15th century. A long line of Nehandas followed, selected by the spirit with an initiatory illness and then ceremonially authenticated.

One of these lion oracles, Nehanda Nyakasikana, led the first Chimurenga (revolt against English colonial rule) in 1896-97. Her forces were victorious at first, forcing Cecil Rhodes to send to South Africa for reinforcements. They came with machine guns and explosives. The Nehand held out longer, but finally surrendered when the suffering of the Shona became too great. The British executed her for what they called "sedition," though she was defending her country agains conquest. She went to the gallows dancing, speaking and laughing.

Shamanic priestesses of East Africa ::: by Max Dashu

The legend of Queen Nyabingi began with an amazon queen named Kitami, who possessed a sacred drum. Later generations revered her as a powerful ancestor (emandua) and she spoke through priestesses called Bagirwa. Most of them were were traditional healers, chosen by Nyabingi as her prophets. Wearing barkcloth veils, they entered paranormal states with "stylized trembling movements" and prophesied in arcane language, with high-pitched voices, holding dialogues with Nyabingi and speaking in her name.

Foreign travellers in the Uganda / Rwanda borderlands heard rumors about these holy women. The explorer Stanley had gotten reports of the WaNyavingi, and of an Empress of Ruanda (though women did not rule there). In 1891, Emin Pasha wrote from Mpororo that this powerful woman was never seen, “a voice behind a curtain of bark cloth, with the reputation of a great sorceress.” Sometimes she was carried on a litter like a queen. A British document refers to “Navingi, chieftainess of Omupundi.”

But there was more than one Nyabingi. Although the bagirwa "were almost invariably women," there were some men too. They also dressed in the female manner. The bagirwa demanded tribute from chiefs, disrupting the tribute patterns in Rwanda, and distributed cattle and beer.Muhumusa

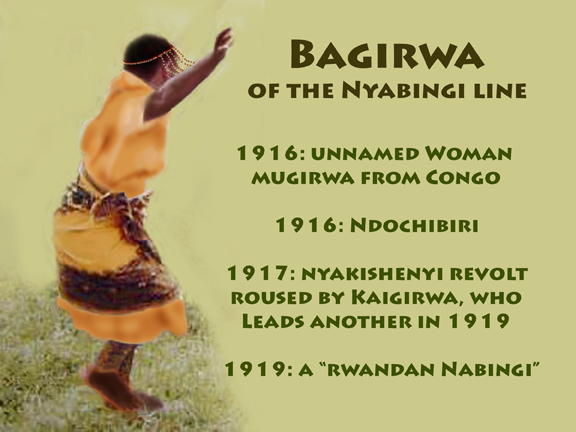

She appears in the early 1900s as a widowed Rwandan queen mother who fled with the heir to the throne into Ndorwa, in what is now SW Uganda. She was a chief who refused to acknowledge the usurper mwame Musinga, who was allied with the German colonials. In 1911 Muhumusa proclaimed “she would drive out the Europeans” and “that the bullets of the Wazungu would turn to water against her.” She roused a military resistance which was stamped out within months, and she spent the rest of her life under detention, first by the Germans and then at the behest of the British (1912-1945).Muhumusa became the first in a line of rebel priestesses fighting colonial domination in the name of Nyabingi. The British passed their 1912 Witchcraft Act in direct response to the political effectiveness of this spiritually-based resistance movement. The graphic above shows a few of the bagirwa mentioned in colonial reports in the second decade of the 20th century.

In August of 1917, the “Nabinga” Kaigirwa engineered the Nyakishenyi revolt, with unanimous public support. British officials placed a high price on her head, but no one would claim it. One commissioner remarked, “These fanatical women are a curse to the country.”

In January of 1919, colonial forces attacked the Congo camp of Kaigirwa, her husband Luhemba, the male mugirwa Ndochibiri and others. The men died in battle, defiantly breaking their rifles and cursing their enemies. But Kaigirwa and the main body of fighters managed to evade the army and escape. However, the British captured the sacred white sheep, which they carefully burnt to dust before a convocation of leading chiefs. They lectured this captive audience “not to listen to Kaigirwa who will only lead them to trouble.” But a series of disasters afflicted the District Commissioner who killed the sheep. His own herds were wiped out, his roof caved in and a mysterious fire broke out in his house. Kaigirwa attempted another rising, then went into the hills. She was never captured.

One official wrote “that a very serious general rising … had been most narrowly averted,” and another referred to “the narrow escape… from a serious native outbreak” and the danger of “this Nabingi propaganda.” Others would follow. The most serious was the 1928 Rebellion, which began with the killing of puppet chiefs and “large, excited and armed gatherings in the hills” and what one British source described as "armed witchcraft dances."

After this, the political dimension of the bagirwa gradually fades, and the underlying healing culture reasserts itself. The missionaries were finally making headway in converting people to Christianity, which had political dimensions. Some converts were not above pressuring people into baptism by declaring that pagans would be under suspicion for political subversion.

But there was one more chapter to follow. Although the Nyabingi movement was quelled by the 1930s in East Africa, it inspired the Rastafarians in Jamaica, who were attuned to the region because of their allegiance to the king of Ethiopia. They adopted Queen Nyabingi as a spirit of liberation whose power would overcome "downpressors." The Order of Nyabingi became an important cultural touchstone. Drumming and chanting Nyabingi took on the meaning of overcoming oppression and destroying those who committed injustice.

Copyleft 2007 Max Dashu. May be reproduced on condition author's name is included.

This nugget is excerpted from Max Dashu's visual presentation

Rebel Shamans: Indigenous Women Confront EmpirePrimary source: Elizabeth Hopkins, “The Nyabingi Cult of Southwestern Uganda”

in Protest and Power in Black Africa, ed. Robert Rotberg and Ali Mazrui, New York: Oxford, 1970